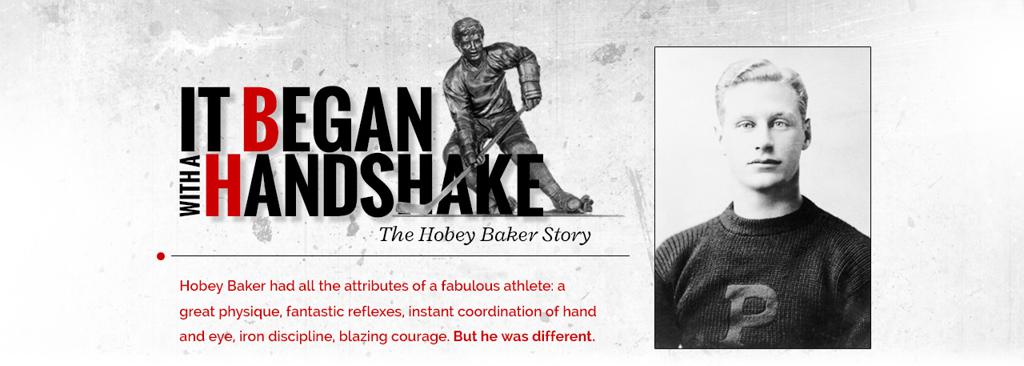

Hobey Baker was the college athlete supreme: The gentleman sportsman, the amateur in the pure sense, playing the game for the sport, who never fouled, despised publicity and refused professional offers. To this day, he is offered as a striking example of the finest that America has produced.

Hobart Amory Hare Baker was born to an aristocratic Philadelphia family January 15, 1892. At age eleven, he was enrolled at St. Paul’s School, the famous preparatory school in Concord, New Hampshire, especially favored by the first families of Philadelphia for the training of their sons. Although remembered as industrious rather than brilliant, Hobey was always in the first third of his class and proved diligent and conscientious.

St. Paul’s pride was its ice hockey team. The school had introduced the sport to America only eight years before Hobey’s arrival. Its teams were outstanding and fared well against college and semi‑professional clubs. Hobey Baker made the squad at age fourteen and was soon its hero.

This was the age of seven-man hockey—no forward passing or substitutions allowed. Ironically, these seeming restrictions best showcased Hobey’s speed, stickhandling and endurance. Also, with someone like Hobey on the squad, the coach was free to experiment with strategies and maneuvers.

Shouts of “Here he comes!” would greet his arrival onto the ice and continue throughout the games whenever he touched the puck. He was simply a pleasure to watch.

For example, he aligned the two defensemen side by side rather than the classical tandem positions of point and cover‑point. Offensively, the standard rush line of four abreast, two wings and two forwards, was altered so the left forward remained on the center line from cage to cage and allowed the right forward (Hobey) to roam all over the ice. These tactics, with the two forward positions renamed enter and rover, were immediately adopted by the hockey world.

From St. Paul, ice hockey spread to other prep schools, and upon graduation, players took the game to the college level. And with it, the fame of Hobey Baker.

While at Princeton, he was not only a legend in hockey, but in football as well. He captained the hockey team for two years and the football team for one. As a punt returner, his coordination and footwork allowed him to take chances and do things others wouldn’t dare.

Page after page was written about him in the newspapers; fans would line up for hours in advance to purchase tickets. Crowds in evening dress would arrive by carriage or limousines when the marquee read “Hobey Baker Plays Tonight.” Yet Hobey remained unaffected. Shouts of “Here he comes!” would greet his arrival onto the ice and continue throughout the games whenever he touched the puck. He was simply a pleasure to watch.

In his era, Hobey Baker was universally recognized as the best amateur hockey player in the United States. At a time when low scoring games were the rule, Hobey set new standards, averaging more than four goals per game. He was penalized only twice in his college career.

His speed and skills dazzled the audiences and the press. The Boston Journal enthused, he “is without a doubt the greatest amateur hockey player ever developed in this country or Canada. No player has been able to weave in and out of a defense, change his pace and direction, with the uncanny skill and generalship of Baker. He is the wonder player of hockey.” At a dinner following his senior year, he was crowned with the laurel “King of Hockey.” In spite of all the well‑deserved praise heaped upon him, he was totally unspoiled by it and he was modest almost to a fault.

After his college years at Princeton Hobey tried his hand in the real world of Wall Street insurance and banking, then the family upholstery business. But he was bored. What sustained him was playing for St. Nick’s, an amateur team in Manhattan. His teammates were ex-Harvard, Yale and Princeton players and a few Canadians working in the city. However, the rest of the league made no pretense of being anything but “semi‑pros.”

In spite of the usual opponent tactic of “get Baker,” Hobey continued his college tradition of making his way to the offender’s locker room to shake hands after each contest. Baker’s aversion to fouling was not because he was stoic or passive, he simply despised dirty play.

Hobey’s skills and daring did not diminish, and he continued his reign as king of amateur hockey. The press still found him -refreshing and remarkable. Following a game with the Stars, the Montreal Press commented, “Uncle Sam has had the cheek to develop a first‑class hockey player. We had always smiled a cynical grin at the thought. A few minutes of Baker on the ice convinced the most skeptical. The blond haired boy was a favorite with the crowd.”

In combat flying, he found even more danger and excitement than he had in contact sports ‑ and Hobey needed both.

The winter of 1916 Hobey’s mind was on a very different sort of competition. Believing American involvement in the World War was close at hand, he took up flying. In 1918 Hobey was commissioned a lieutenant in the Army. He was assigned to the 103rd squadron. He was as adventurous a pilot as he had been an athlete, chosen on occasion to exhibit aerial acrobatics with his friend Eddie Rickenbacker. In combat flying, he found even more danger and excitement than he had in contact sports and Hobey needed both. He was officially credited with bringing down three enemy planes and was decorated with the Croix de Guerre for valor for “exceptional valor under fire.”

Following the armistice, his orders home in hand, Hobey announced to his fellow officers he was going to take “one last flight in the old Spad.” His mates were quick to argue with the young captain who was challenging the oldest tradition of the air service—never take a “last” flight lest it be just that. But they were not able to dissuade him and were even more upset when the plane he insisted on flying was a borrowed one, just out of the repair shop.

OUR TRIBUTE TO “THE WONDER PLAYER OF HOCKEY”

THE HOBEY BAKER VIDEO

Tradition was not to be denied the final victory that gray, dismal day over Toul, France. Just a quarter mile out, the engine quit and the plane crashed. Hobey Baker, age 26, died in the ambulance a short time later.

In 1919 he received a posthumous Army citation from General Pershing for distinguished service and exceptional gallantry.

With his death in France, the old‑fashioned virtues Hobey Baker personified took on legendary qualities. He was one of the first Americans selected to the Hockey Hall of Fame, in 1945. In 1973, the United States Hockey Hall of Fame in Eveleth, Minnesota included Hobey Baker as a charter member.

The Sports Bay and Chapel in the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City was dedicated in 1951. Hobart Baker was one of four men whose name was cut in the walls of the chapel to serve as a constant expression and reminder to all future generations of the highest ideals of character and sportsmanship.

No finer example of the true sportsman may have ever been developed in American athletics. Whatever game he played he always played it first of all for the joy of the sport.